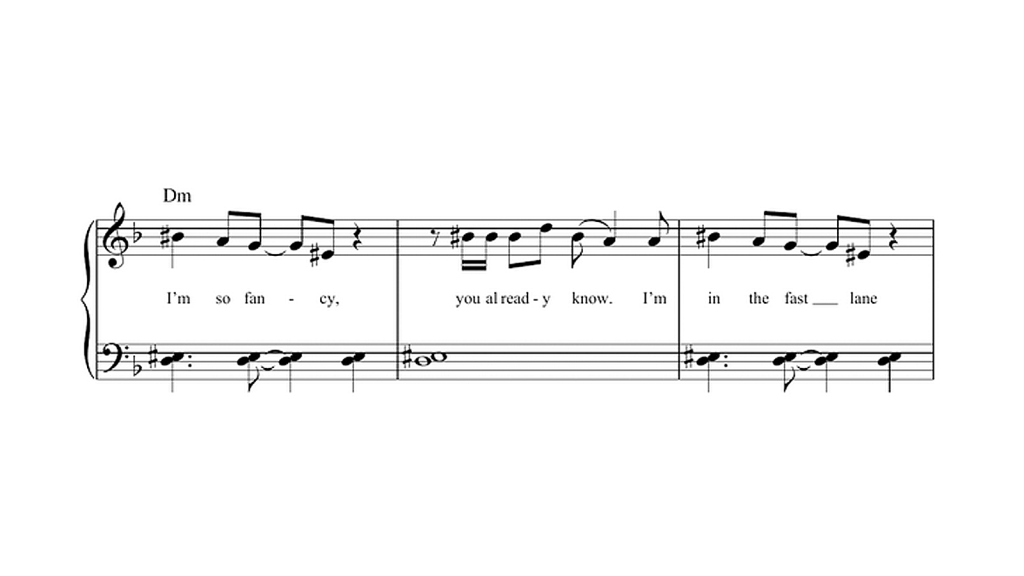

I might call myself a poet, but I hardly read as much poetry as I do listen to music. That is not to say that there isn’t poetry in music, and vice versa. In the poetry workshops that I facilitate for aspiring poets, I often start by showing a sheet of music, then ask them what they see: meter, movement, intonations. These are all facets of poetry. It becomes more apparent when I show the same sheet of music with lyrics. Then the lyrics on their own. Do they not appear as poems? Are poems on the page not instruction just as it serves a musician?

I have always had a penchant for lyrics (I am now imagining a chanting pen). It was being perplexed by Kurt Cobain’s lyrics that made me seek out songmeanings.com way back in the early 00s. I would sit and read the comments where users would have a go at interpretation. Simultaneously, I had begun reading the Quran in English translation, and even there, I would always look at the footnotes, where there would not just be historical context but also interpretations. This was my introduction to close-reading, and by extension close-listening. It was certainly not the English Literature lessons in school (sorry, Ms. Sandra, you were lovely but that curriculum simply did not capture my imagination). And so, I would listen.

Early on, it was the words that would be the center of gravity in a song. I would feel viscerally the emotions, expressions, the imagery. Perhaps it was all the hormones of adolescence and the particular life experiences I was relating to. Sometimes it was escape, and fantasy. But a lot of the time I needed it to feel real, to delve into depths. In retrospect, this pigeon-holed my listening behaviour. I had ill-conceived notions of which genres of music were able to best do this, and I would listen far and wide but only within those genres. Today, to be honest, it is rare that the lyrics register, let alone that I tune into them to listen to their story.

Over the years, I have learnt to hear stories that only notes, and sometimes the silence between them, can tell. To access certain states of mind, sensations in the body, and perceptions of time, through music. It is utterly fascinating to me that so much has been explored in terms of musical worlds, and worlds that can be explored through music. And yet, there are not as many opportunities, sitting in Colombo, to experience them. Our radio stations, promoters, and other gatekeepers of music, do not seem as interested in these possibilities. It is a very few folks who are around who put in the effort to make these worlds accessible to others. To share their passion for its possibilities. And they do so despite the fact that it is not sustainable, let alone profitable. I have so much respect for those who do this, even when crowds dwindle as they lose interest and move on to their next fix.

Attention, Hyper-fixation, and Discovery

It feels ironic to write about attention in a long form essay when our minds have been subjected to the brain rot of fast-moving content for years upon years. I’m not immune to this. I have an active addiction to TikTok and Instagram, but I try to make the effort to sit and read. To spend time with books. To listen to an entire album. Yet this behaviour is becoming far less common outside of those with niche interests. Yes, there has been an uptick in certain areas like the resurgence of interest in physical mediums, be it CD, vinyl, or even cassette, but we are not talking about mass adoption here. It is also prohibitively expensive for independent artists to release their music in such mediums, as well as for listeners to engage in that kind of consumption culture.

My general observation, stemming from conversations with Gen-Z music lovers, and following way too many accounts on Instagram, is that we seem to be hyper-fixating and I suspect that it is not fully within our own agency. Of course, there are always larger cultural trends that inform how we engage with culture, our habits, our desires, and such, and perhaps we are always negotiating our agency within it. Still, it feels as though these external forces are further bolstered by techno-fuedalism. How much of our interests are actually our own? When you get annoyed that your ‘favourite song’ became TikTok famous, do you feel betrayed by the algorithm?

Or do you instead cast your condemnation and condescension upon the masses who are lapping up the latest trending background track for a dance meme? Does having a ‘favourite song’ of an ‘under-rated’/’undiscovered’ artist really evince an engagement with music? I find it amusing and quite disturbing how many times I have seen Gen-Z gripe over this phenomena. As a musician myself, I can understand how a song going viral on TikTok has very real economic impacts on the musician and their career. It strikes me as rather selfish for one’s favourite song to be ‘ruined’ by other people’s appreciation of it (however shallow or deep it is to any party involved, including the musicians).

Moving on, given that we have now come out scathed by the year that was “brat”, I cannot write this newsletter without acknowledging my own fascination with hyper-pop and how it scratches that 2000s kitsch itch that it has made me aware that I had. Reading Simon Reynolds’ “Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past” in tandem with “Futuromania: Electronic Dreams, Desiring Machines, and Tomorrow’s Music Today”, one could argue that hyper-pop fits into both the frameworks of retromania and futuromania, where pop culture is obsessed with recycling and reinterpreting the past. Hyper-pop takes past musical elements — hooks, melodies, structures — and pushes them to extremes. Music’s past is available in ways never before possible: searchable, archivable, consumable at will. Hyper-pop doesn’t simply mimic the past; it hyper-accelerates it, combining nostalgic influences with futuristic sounds. It’s plundering the past and the future simultaneously, creating something that’s both referential and original.

Yet the insight that is unearthed, for me, through this, is that hyper-pop reflects a cultural restlessness. Yes, there is an over-reliance on the past, but hyper-pop’s chaotic, genre-blending nature can also be seen as a challenge to the conventional understanding of history in pop music. By distorting the past into extreme forms, hyper-pop forces a conversation about how the past is endlessly available, consumed, and reimagined. It’s nostalgia, but not as we’ve known it — frenetic, radical, and at times unsettling. Yet is a very particular nostalgia that is steeped in a very specific cultural hegemony that has been a soft power tool for powerful nations such as the US.

Is there a more appropriate genre for our present state of mind? When the elites have captured our attention, controlled its span, and continue to feed us the past in such innovative ways that we can hardly imagine a future that can be free from it? I personally do not find hyper-pop to be a liberating genre of music. It feels to me self-aware of what it is doing and the age in which we are stuck in. There is something also hyper-violent about it. It literally sounds to me like a thesis on what is happening to our brains.

A study by MusicThinkTank found that 57% of listeners changed their music preferences after using algorithmic playlists, suggesting that these recommendations are shaping listeners’ tastes, which could lead to a homogenization of music preferences. Algorithmic playlists account for 61% of programmed listening, meaning more than half of streams generated from playlists come from algorithmic recommendations. What will be our next hyper-fixation? And what forces are at play to dictate it?

In “The Age of Surveillance Capitalism”, Shoshana Zuboff discusses the exploitation of personal data by corporations. Applied to the music industry, where listener data is harvested to both predict and influence consumer behavior, does it not raise ethical questions about autonomy and consent? I’ll return to this notion in the next section.

In the digital age, our attention has become the most exploited resource, the commodity on which the entire economy of attention is based. The attention economy relies on an intricate system of algorithms designed to captivate and retain users’ focus, often to the detriment of their well-being and autonomy. The digital platforms, from social media to music streaming services, have commodified the very essence of human consciousness. In the blink of an eye, our desires, our preferences, and our behaviors are mapped, monetized, and manipulated, reducing us to mere data points in a larger capitalist machine.

Social media platforms and streaming services like Spotify function as attention factories, engineering experiences and content that cater to instant gratification. These systems exploit our need for connection, novelty, and escapism — capturing fleeting moments of joy and despair, to turn them into predictable patterns for profit. The music we listen to is not just a reflection of our tastes, but a product of complex algorithms that seek to manipulate our emotional state, nudging us into consuming more, feeling more, and buying more. Through music, through images, through likes, we are encouraged to participate in a cycle of consumption that further entrenches us in the global capitalist system.

Decolonizing the mind in this context means breaking free from the digital cycles of addiction that these platforms foster. It requires reclaiming our attention from the systems that exploit it, fostering deeper engagement with music and culture on our own terms, rather than through the lens of profit-driven platforms. The question is not how we consume culture, but how we can reimagine our relationship to it — not as passive consumers, but as active, conscious creators and participants in the world we shape.

In Liz Pelly’s “Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist”, she dissects Spotify’s grip on music consumption and its impact on listeners and artists. A critic of the streaming economy, Pelly argues that Spotify’s goal isn’t hits but monopolizing attention with curated “chill vibes.” Drawing from her D.I.Y. ethos, she critiques the platform’s winner-takes-all model that sidelines artists and homogenizes creativity. Yet Pelly’s sharpest concern lies with listeners. Spotify’s innovation lies in mastering affect — using music to modulate mood, whether hyping up, calming down, or dissociating. Unlike record labels, Spotify prioritizes sustained engagement over artistry, thriving on ambient loops as much as hits. By optimizing for passive listening, the platform reshapes how we experience art, reducing music to a tool for keeping us tuned in.

But wait, Spotify has helped so many artists get discovered! Yeah, by extorting artists and independent record labels to pay to appear on ‘curated’ playlists. They literally have enough data on listener behaviour to be able to cater to each individual’s respective tastes, interests, identity, region, to the point that it could take an artist’s upload of their album and then map out exactly where they will find their listeners, similar artists, appropriate record labels. All that data could be a massively productive force towards actually connecting people with art, but instead it is used to plunder and plunder and plunder.

Here’s a fun fact. A lot of the early recordings that we have of music around the world has a colonial legacy. It was our colonizers who would record indigenous music traditions and press them to shellac phonographs. There’s a brilliant collection of these by Excavated Shellac that you can acquire physically as vinyl or digitally, if you’re curious to hear those early recordings. What’s fascinating about these recordings is their length. Given the limitation of the shellac form, these recordings were truncated into 3 to 5 minutes. What are the implications of this given that many musical traditions were ritualistic and spanned for far longer durations? Both the performers and the recordists would then become involved in editing down and trying to fit a temporal experience into this limited technology. Is it not strange how the duration of songs has changed over time? How form has literally dictated content because of developments of technology? Today, we have songs that are 90 seconds long, thanks to TikTok and even the coining of the “TikTok drop”. It is not just the length of music that is informed by the technology but also its structure itself. How did we go from hours long qawwali performances to 90 second loops? And what have we lost along the way in how much attention we can expect from a ‘listener’?

Reading Achille Mbembe, Frantz Fanon, and other decolonial thinkers, we come to understand how colonial systems commodified and consumed African bodies and cultures. Colonialism was fundamentally an economy of capture, extraction, and consumption of the other.

Has anything changed when we consider how music streaming platforms commodify local and indigenous music without fairly compensating its creators or contextualizing its cultural origins? Are we supposed to be appeased with Spotify’s lazy repackaging of ‘localness’ in how it ‘curates’ its Sri Lankan playlists? Are we ever going to open up the can of worms of the political implications of this in relation to what sounds are represented? When is the Spotify Sri Lankan Bus Music playlist going to drop? When will they stop taking down Eelam Music from the platform? When will someone have the courage to actually put these musical worlds into conversation with each other to understand the trajectories of nationalisms and cultural hegemonies? When is this doomed nation going to reckon with how music cannot escape the war? How it cannot escape genocide? Spotify removing Eelam Music from its platform is an act of erasure. (It has since been recovered after backlash.) But it is not just Spotify that is doing it. When was the last time you heard or even listened to that ‘genre’? When was the last time you listened to an Eelam Tamil person, let alone their artforms? Do you still understand Tamil? Or do you prefer when your Eelam Tamil artists sing in English with just enough Tamil so you don’t mistake them for the Grande venti-latte Spotify decides to autoplay?

Okay, breathe.

Can we consider this from a decolonial perspective? In what ways has this technological determinism destroyed musical worlds? (Or maybe you would prefer the term ‘transform’? And, if you do: yuck). What ways have our techno-feudal overlords continued this colonial legacy and how do we imagine escaping their stronghold? Not just as listeners, but as musicians, too. What do we need to take back?

Data Rights, Data Worlds and Artists

The disturbing fact is that we are constantly reduced to numbers. We are statistics. We are data points. This is the resource that we have been giving away in return for ‘free’ services. We do not read the terms of service agreements. We just accept them. We are passive in this way too. And now we have to reckon with the world that this passivity is creating.

In “The Costs of Connection”, Nick Couldry and Ulises Mejias introduce the concept of “data colonialism,” framing digital data extraction as a continuation of colonial exploitation. Data colonialism appropriates human life through data for capital accumulation on an unprecedented scale. Let’s consider this in relation to how listener data is harvested and used to shape music recommendations, prioritizing profit over, for instance, cultural diversity, equitable opportunity, or very simply how this data is ‘owned’ by these corporations, and all we are offered is the shiny distraction of Spotify Wrapped at the end of the year.

Problematic perhaps for his dreadlocks, yet at least he speaks out for Gaza, something of a tech legend, Jaron Lanier, in “Who Owns the Future?”, makes a compelling case for reclaiming ownership of the data we generate — a radical proposition for a digital age where data is currency and we are its unwitting miners. Lanier describes a world dominated by “Siren Servers”, large tech entities that extract, monetize, and hoard our data, leaving creators and contributors in the shadows of their own value. His vision, however, is different: a digital ecosystem where individuals, including musicians, are recognized and compensated for the data their creativity generates.

For musicians, this strikes at the heart of how platforms operate today. Streams and algorithms generate immense wealth, but who benefits? Rarely the artist. Lanier argues that a fair system would allow creators to own not only their works but also the data surrounding their engagement — every listen, every algorithmic insight— ensuring that value flows back to its rightful source.

This isn’t just about economics; it’s about dignity. Lanier believes that data ownership is key to reshaping how we value creativity, fostering a digital world where individuals — not faceless corporations — hold the reins. His critique of our current landscape is sharp: a system built on appropriation cannot sustain fairness. And yet, he offers hope for an alternative — a future where we are not just participants but stakeholders in the music we create and consume.

Now let’s get into the belly of the very specific beast we are talking about. What insights do former Spotify employees have on this? Glenn McDonald, former Data Scientist at Spotify, (known for everynoise.com that for 10 years harnessed Spotify’s data points to allow for creative ways to explore music), argues that “your data is yours” — generated by your actions, tastes, and online presence. Public data contributes to collective knowledge, but it’s not a replacement for personal ownership. He insists, “You are entitled to both your public and private data,” with the right to transparency in its use. Private data requires informed consent, and platforms like Spotify should provide users with clear, verifiable explanations of how their data is used.

Spotify’s current model, McDonald critiques, is one where “you < corporations > software > your data.” He envisions a better system: “you > your data > software > corporations.” This shift requires democratizing data access, creating a shared framework for discussing algorithms and data logic — not dissimilar to how we use math to discuss numbers.

McDonald’s project Curio puts this into practice, offering users full transparency and control over their data. “Every bit of data Curio stores is also visible directly,” he says. It’s a step toward a world where users — not corporations — shape their experiences, and data serves the collective potential rather than corporate goals.

As McDonald concludes, “I’m totally sure of almost nothing. But I’m pretty sure we only get dreamier futures by dreaming.” His call to action: a future where data ownership and creativity are in the hands of the people, driving innovation for all.

The imaginings coming from those engaged in the tech world remind me of bell hooks when she writes in “Art on My Mind”: “The function of art is to do more than tell it like it is — it’s to imagine what is possible.” How do we reckon with how much our imagination has been limited by the ways in which we engage passively with technology? How do we empower musicians and music tech idealists who actually have the active imaginations that can realise these possibilities? Is it up to us? Is it time to take back our attention? To take back our data? To take back our imagination?

Moving Music and my AOTY

Let’s return to music. Let’s return to poetry. Let’s return to language. People love to call music a ‘universal language’ as they take in their NYE empathogenic trip amidst IOF soldiers escaping their genocidal duties, so let’s really extend this metaphor. In “Decolonising the Mind”, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o questions how global systems privilege certain “languages” over others. This has implications for literature (Fuck Shakespeare, get over yourselves.), for popular music (There is music outside of the US, and representation doesn’t mean only giving opportunities to diasporic artists living in centers of power. Sure, that’s one step in reparations for being responsible for displacing them from their lands and their cultures in the first place, but it’s high time that these resources are shared with those left behind), and for culture (We do not talk about global monoculture enough.)

Thiong’o says “Language as communication and as culture are then products of each other. Communication creates culture: culture is a means of communication. Language carries culture, and culture carries, particularly through orature and literature, the entire body of values by which we come to perceive ourselves and our place in the world. How people perceive themselves and affects how they look at their culture, at their places politics and at the social production of wealth, at their entire relationship to nature and to other beings. Language is thus inseparable from ourselves as a community of human beings with a specific form and character, a specific history, a specific relationship to the world”.

I’m not unaware of the irony of writing this in English. It’s the depraved reality of this world that we need to use this language to communicate across cultures. It is an incredibly violent world to have arrived into. To be severed from your mother tongue, your mother world, a mother wound, as M. NourbeSe Philip would put it. So what does it mean that English pop music is producing the lyrics that annotate your Instagram posts? That you feel ‘seen’ and ‘heard’ when a hijabi-clad Canadian citizen talks about genocide while sounding hardly dissimilar to the white genocide apologist over in Connecticut? Not simply in language employed, but the sonic texture of voice, musical scale, any connection at all to an ancestry of sonic worlds that far surpass this moment of hell that we were born into. Thiong’o says “the choice of language and the use of language is central to a people’s definition of themselves in relation to the entire universe.”

Thiong’o describes English in Africa as a “cultural bomb” that systematically erases indigenous histories and identities. Thiong’o writes, “The effect of the cultural bomb is to annihilate a people’s belief in their names, in their languages, in their environments, in their heritage of struggle, in their unity, in their capacities and ultimately in themselves”. This cultural violence, he argues, leaves colonized societies as “wastelands of non-achievement,” fostering a profound desire to escape that “wasteland”. Oh, to be a star in the USA. To be discovered by a major label and tour the states, Europe, those lands of prosperity. What dreams we have been reduced to.

Thiong’o calls this “colonial alienation,” a deep separation of the mind from the body, enacted by the “deliberate disassociation of the language of conceptualisation, of thinking, of formal education, of mental development, from the language of daily interaction in the home and in the community”. This alienation is, in his view, a societal condition where “bodiless heads and headless bodies” coexist, trapped in different linguistic realms, disconnected from each other and from their cultural heritage. And what does this imply for music? Your universal language? How did it become so… universal? Can you beat-match bodiless heads and headless bodies?

Breathe.

Now, let’s listen to other worlds.

We start in Iran, with an album from 2012, yet one I only ‘discovered’ in the past year. Here is an artist who seems to be looking back while looking ahead. He is considered a master of the ancient music of his native Iran, a virtuoso player of the kamancheh, a small, bowed, spike-ended fiddle. Yet, he does not stop at mastery alone, and is not static in preserving the classic music, instead becoming one of Persian music’s supreme innovators.

We cannot talk about this music without considering the significance of music coming out of Iran at all. We have to grapple with the violent history of this nation and its relationship to music. The Islamic Revolution in Iran deeply transformed the music culture, subjecting musicians and fans to cycles of official condemnation, limited encouragement, and grudging tolerance of traditional and classical music. For artists like Kayhan Kalhor, this meant navigating a complex landscape of restriction and repression. Initially, Kalhor left Iran to pursue music, living in Italy, Canada, and New York before returning to Tehran years later. Despite his avoidance of overt political statements, his album “I Will Not Stand Alone”, recorded in Tehran in 2011 amidst the aftermath of the Green Movement’s bloody repression, serves as a poignant reflection of that period. Kalhor describes it as a response to “one of the most difficult stages in my life, where darkness and violence seemed to be taking over.” Yet from this experience of isolation, he chose to “be with people and play music for them,” seeing his role as connecting culture to community, offering music not necessarily as a political statement, but rather as a bridge between individuals during a turbulent time.

And let’s not romanticize Iran in the context of this genocide and by virtue silence the voices of not just its women but also that of Kurdish separatism. Let’s instead listen closer. Hani Mojtahedy’s “HJirok” is a deeply personal yet politically charged album, drawing on her memories of growing up in the house of her grandfather in Sanandaj, Iran. After fleeing the region in 2004, Mojtahedy, together with producer Andi Toma, used her childhood experiences and the rhythms of Sufi music to craft an album that connects the past with a hopeful future. The music taps into centuries-old traditions, particularly Sufi drum rhythms and setar melodies, which have served as cultural pillars throughout the Kurdish diaspora. As Mojtahedy explains, “HJirok” is rooted in the figures of the Sufi dervishes, “a culture that precedes today’s political, social, cultural, and religious systems.” The album serves as a rejection of political and cultural oppression, offering both a personal and radically universal utopian promise.

At the heart of “HJirok” is a desire to transcend political and social strife, as well as the violence that has defined Mojtahedy’s life as a Kurdish woman. After the brutal suppression of the Kurdish rebellion in 1979, her family’s home became a sanctuary from the political turmoil of post-revolution Iran. This longing for peace and equality is mirrored in the album’s lyrics, written in both Kurdish and Farsi, symbolizing a bridge between cultures. Mojtahedy’s avant-garde vocal techniques and Toma’s digital manipulation of field recordings further the album’s thematic focus on emancipation. With “HJirok”, the artist creates not just a sonic landscape, but a vision of a better, more egalitarian future — one where diverse cultures and soundscapes can coexist in peace. The project is an invitation to enter this non-place, a metaphorical home for all who wish to join in the promise of liberation and unity.

And, finally, what we cannot turn our ears away from. This is my AOTY. Akram Abdulfattah, a Palestinian-American violinist and composer, creates music that resists the cultural bomb — an act of decolonization in potent form. As a young artist emerging from the violence of Palestine, his sound is a reclamation of identity through the language of music, not words. In a year marked by genocide, to release an album as a Palestinian is to not speak in the language of violence or oppression but to use music as a medium for peace, justice, and resilience. His newest album, “Abu Kenda”, contrasts hope with pain, joy with sorrow, pulling from the depths of his roots while also crossing boundaries and being in conversation with other musical worlds, dominant ones, in fact. The music blends Palestinian and Arab classical traditions with jazz, rock, and funk, constructing a sonic world that speaks of both personal and collective struggle. This fusion can be thought of as both temporal and sonic bridging across cultures, an appeal that says: Listen, I will even bend this string so that your ear may hear it.

Abdulfattah’s fusion of these elements reflects a larger resistance to the erasure of Palestinian culture, offering a space for a new kind of narrative — a narrative built on survival, harmony, and freedom. It’s an album born in the shadow of war, but it refuses to be defined by it. With “Abu Kenda”, Abdulfattah doesn’t just make music; he makes a statement about the persistence of Palestinian cultural identity and the enduring fight for justice. As a virtuoso violinist, he channels the energy of his heritage through a global lens, reaching out to the world to connect, to heal, and to resist. His journey from the Galilee mountains to the world stage is not just one of personal achievement but an act of cultural defiance — resisting colonial erasure by asserting, loudly and clearly, that Palestinian music matters, and that resistance, through art, is an essential act of survival.

Leave a comment